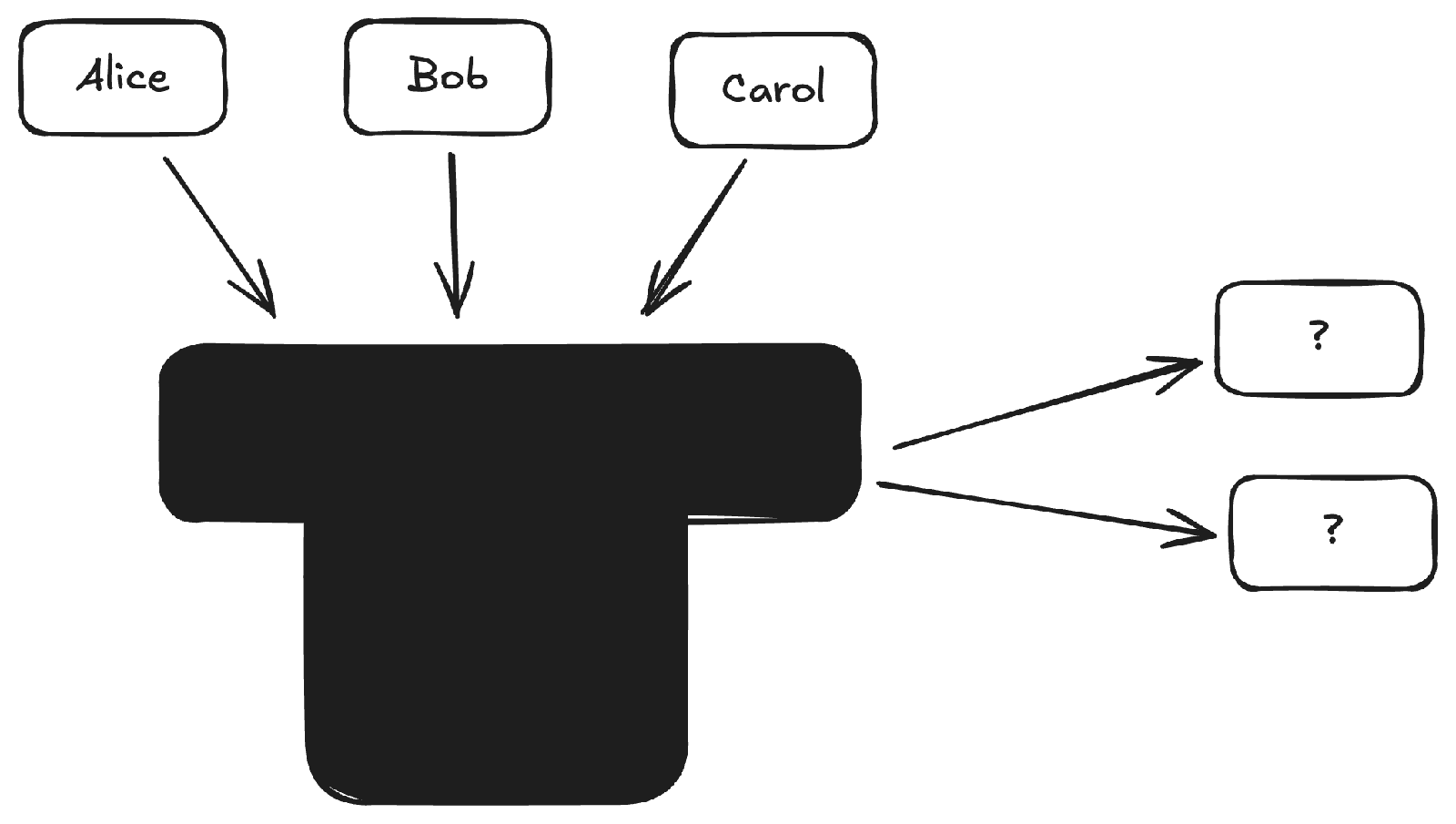

I was thinking about an approval-style voting system that could end with a large number of ties, and ran into the problem of how to break ties in a provably-fair way that doesn't depend on candidates trusting each other and won't make voters' eyes glaze over.

I think I found a solution which is provably-fair, but it might still cross over into eye-glazing territory. I don't know if this is practical (or novel), but I'm writing it up in case anyone else finds it interesting.

A Bad Solution: Papers in a Hat

The most obvious solution is to write names on pieces of paper, throw them in a hat, then select names until you have enough winners.

Unfortunately this is far from provably fair. Whose hat do you use? Who picks the names? If you shake the hat, who shakes it? If you ensure the paper is all identical, who provides the paper?1

Even if you can solve these problems, will everyone believe you?

It seems like the hard part is that we have one source of randomness (the person-hat-paper system) which needs to be fair.

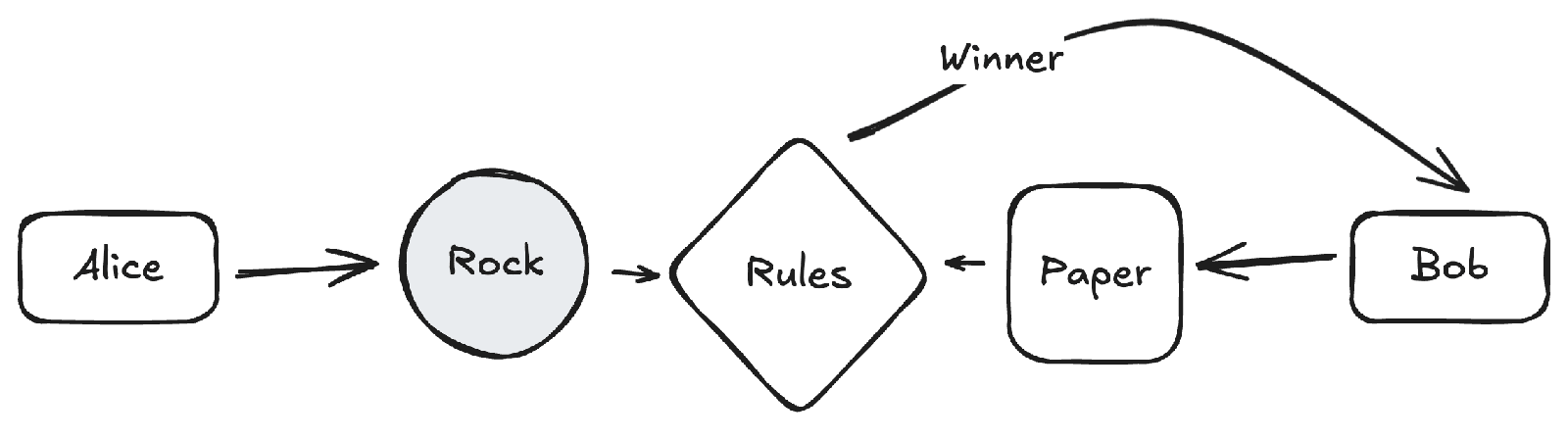

Rock Paper Scissors

What if instead of one source of randomness, we have each candidate provide their own?

Maybe instead of one person-with-a-hat randomizer, we could have each candidate be their own randomness source. We just need a way for candidates' randomness to be merged in a way that determines the winner.

Conveniently, we have just such an algorithm: Rock-Paper-Scissors.

Each candidate picks one of three options using their preferred random number, and then we apply known rules to determine the winner from any combination. Assuming random selection, every outcome is equally likely.

Standard Rock-Paper-Scissors has the undesirable property of having an element of skill, but we could fix that by letting candidates secretly write their choice on a piece of paper and use any randomness source they want (like a fair die2). Since the winner depends on both choices, if either candidate picks their choice randomly, then the result will be random.

So, problem solved. This will work and is provably fair as long as either candidate wants it to be. Unfortunately, it has two properties that make it slow:

- It's possible for the game to end in a tie, requiring it to be repeated (potentially an unbounded number of times).

- It's complicated and time consuming to scale this to a multi-way tie while maintaining an equal chance of victory for all candidates.

So let's start by fixing the potential tie problem.

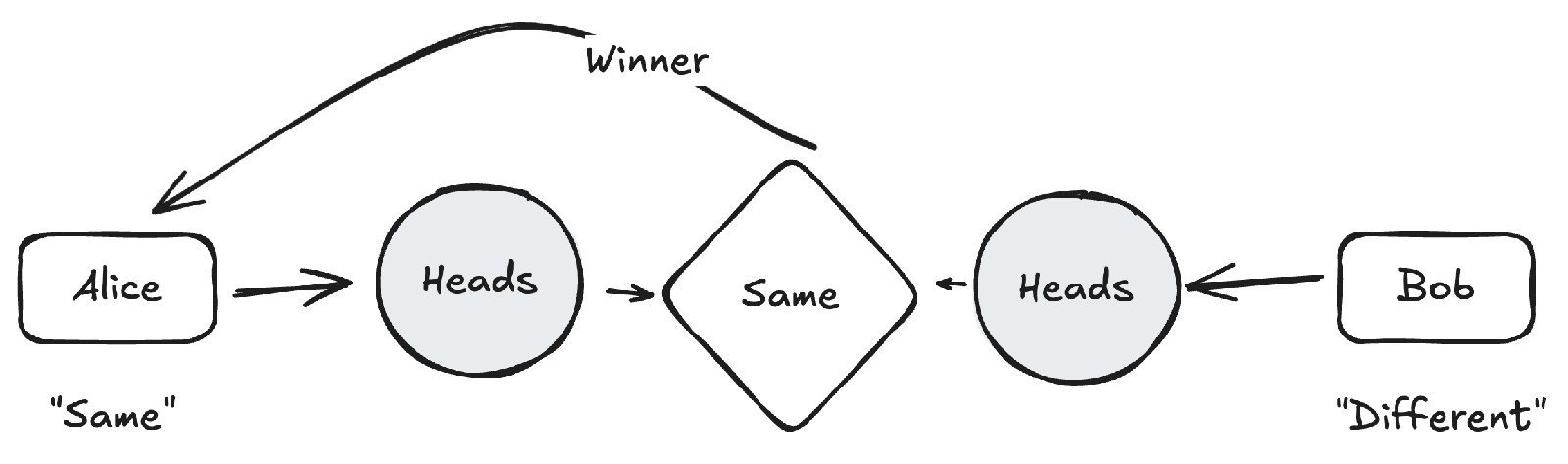

Binary Rock-Paper-Scissors

In our previous example, candidates are selecting between three options and then using a complicated system to decide the winner. Can we instead have the candidates work together to select a winner directly?

Let's arbitrarily3 assign each candidate either "same" or "different". Then both candidates provide their own coin and flip it. If both coins show the same side (heads-heads), the candidate assigned "same" wins. If they show different sides (heads-tails, tails-heads) the candidate assigned "different" wins.

Since each outcome has two ways of occurring, both candidates have the same chances, and because the result depends on both coins, only one of the coins needs to be fair to ensure that the result is fair4.

This is better, and still seems easy enough to explain, but we’re still stuck running a complicated tournament for multi-way ties. Is there some way that we can instead make the candidates work together to fairly “pick names out of a hat”?

Picking Numbers Out of a Hash

Ok, so we finally need to do some math, and I can’t figure out how to intuitively hide it behind coins and dice.

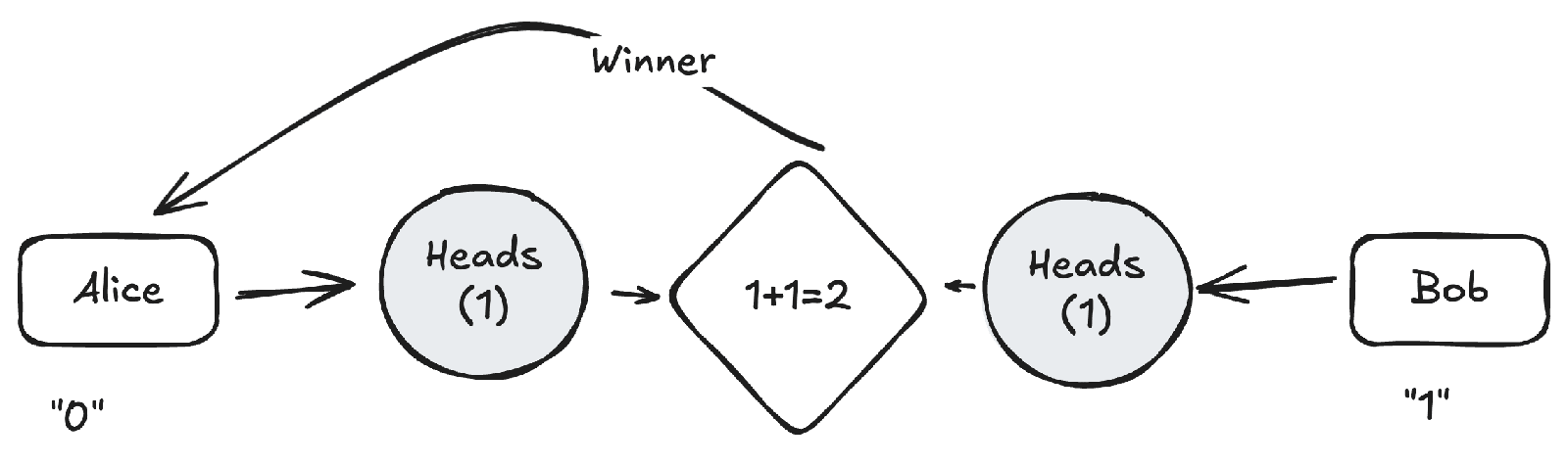

In our last example, the nerds in the audience might have noticed that we used coins to create a one-bit cryptographic hash function.

A hash function is a math function that takes some number of inputs and gives us a shorter output. The coins also create a very convenient hash function where the output always depends on every input (i.e. you can't determine the winner from only one coin, you need to know the results for both).

The coin algorithm is equivalent to a hash function that that takes two binary numbers (0 or 1) and returns another binary number. Say heads is 1 and tails is 0. Flip two coins, add the numbers up. If the result is even (0 or 2) then player 0 wins and if the result is odd (1) then player 1 wins.

This unfortunately sounds more complicated than “same” or “different”, but the advantage is that now we can extend the numbers.

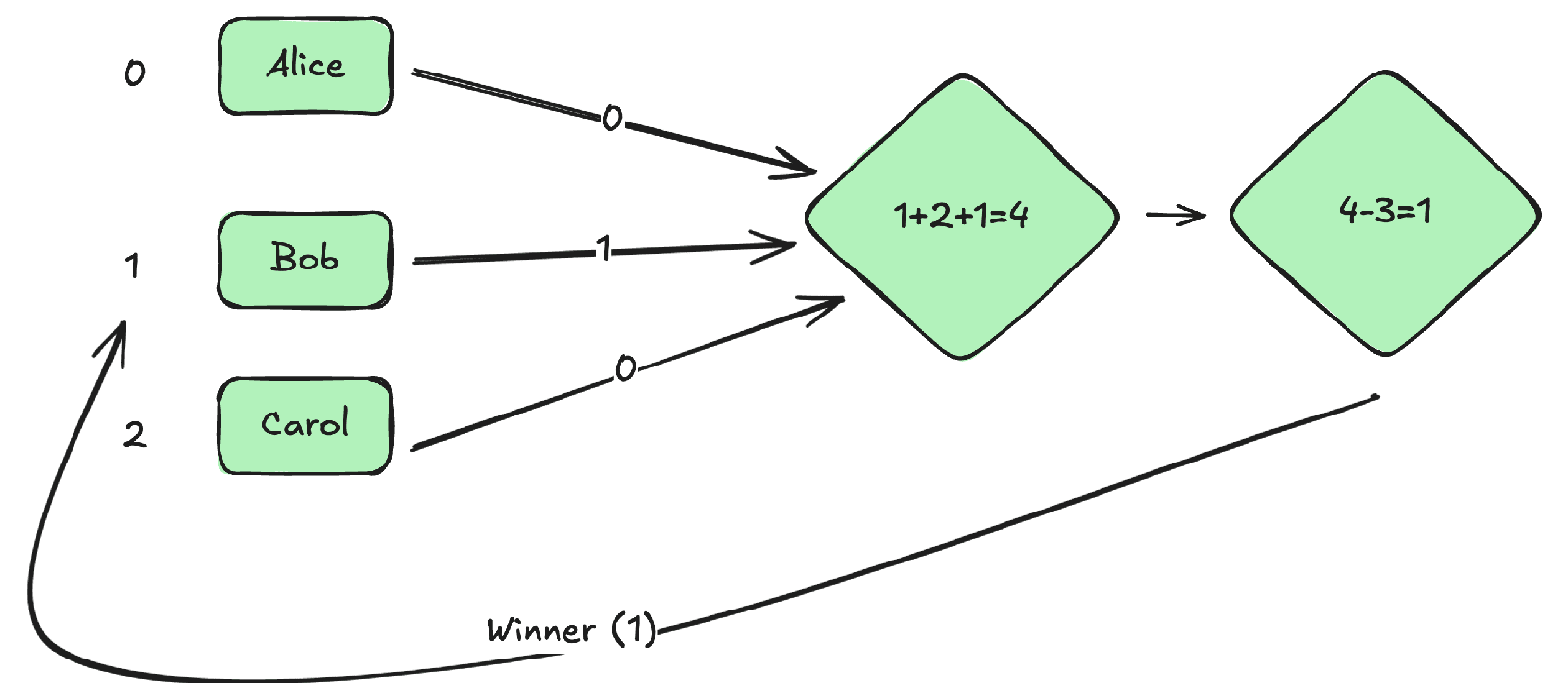

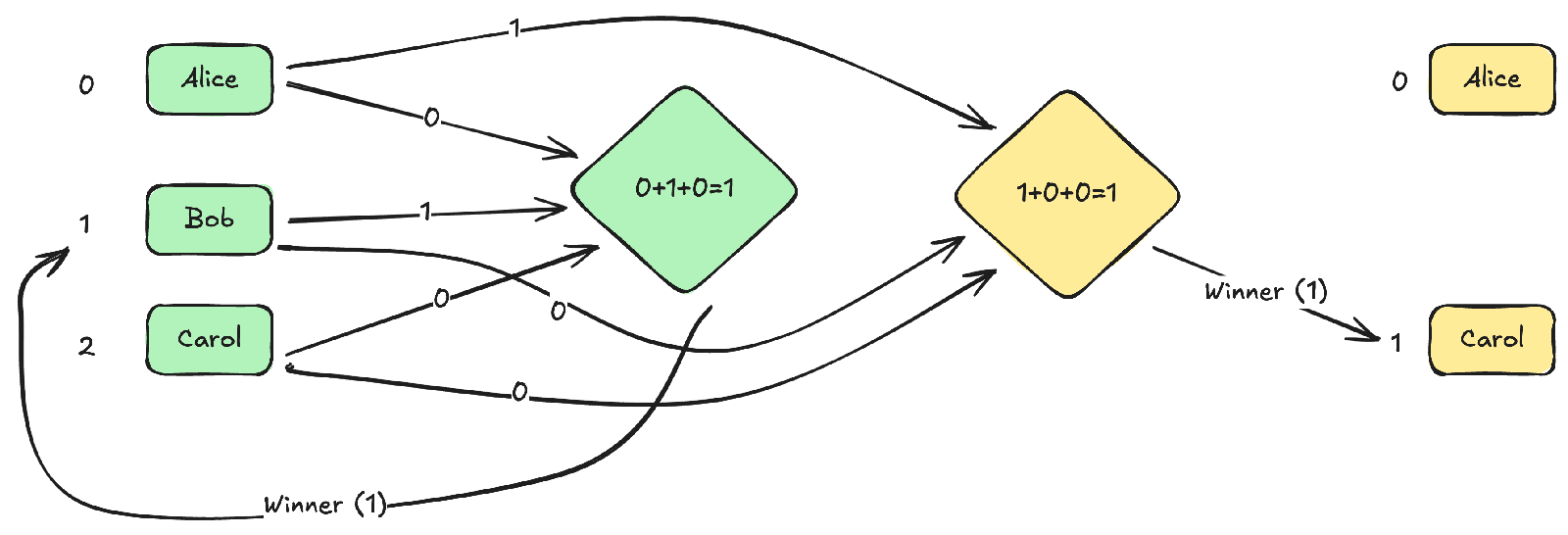

Say we have three candidates. Arbitrarily3 assign them the numbers 0, 1, and 2. Have each candidate write a number from 0 to 2. Simultaneously reveal the numbers and then add them up. If the number is larger than 2, subtract 3 until it’s in the range 0-2. The winner is whoever’s number comes out.

Want to select 2 winners out of three? Have each candidate write two numbers: A number between 0-2 and another number between 0-1. Use the first number to pick the first winner. Renumber the remaining candidates by shifting down (if necessary) to get them into the range 0-1, then use the second number to select the second winner.

You can extend this to any number of candidates by writing larger numbers, and you can extend to any number of winners by writing additional numbers.

All of the numbers should be made public and anyone can verify the math (which only requires basic addition and subtraction).

Conclusion

That’s the algorithm I came up with. I’m reasonably happy with the result, although it’s a little math-y and not ideal that to select 50 candidates from a 100-way tie, you need every candidate to write and add-up 50 numbers.

If we want to result to be faster but less deterministic, there are tricks to remove approximately half of the candidates every time5, but you could run into a lot of repeats if the algorithm removes too many candidates.

Is this a good solution? I'm particularly curious if anyone has an idea that's as intuitive as the coin flipping version. Also, is this actually useful in any situation besides my oddly-specific approval voting daydreams?

You could also use a robot to select the papers, or number people and use a random number generator, but this is actually much worse since it's even harder to prove that the digital "hat" hasn't been tampered with. ↩

Roll a D6. If you get 1-2, pick "rock", 3-4 "paper", 5-6 "scissors". ↩

When I say to arbitrarily assign a candidate some condition, random selection is one way to do it. The important thing here is that as long as you do the assignment before running the rest of the algorithm, it doesn't matter how you make the choice and it doesn't need to be "fair". ↩↩

To prove this, consider if one candidate uses a double-heads coin. If the other candidate flips heads, the result is "same" and if they flip tails, the result is "different". So, even a perfectly unfair coin gives you a 50% chance of winning. ↩

Each candidate picks "odd" or "even", then they all flip a coin. Count the number of "heads". If the result is odd, the "odd" group wins, otherwise the "even" group wins. ↩